Sights & Sounds from the Site

Walk with my friends and me… Boots clap on the pavement as nearly 20 of us begin earnestly walking our daily, morning route here in Jerusalem. There’s a clamor of excited voices. Fresh sights, fresh sounds. The dark of the night is quickly being overtaken by the morning.

The great moments of this walk come near the end – as we ascend to the Temple Mount area. On a clear day (which is rare) you can see the country of Jordan from the peak of the hill above me.

Over the months, I have become keenly aware that three religions are playing King of the Hill on these ancient mounts. Various Christian cemeteries dot the hill around me. Many Jewish edifices and synagogues stand in the Old City just ahead. A minaret rises from the Kidron Valley to my east, glowing with seemingly-out-of-place neon green bulbs. Ah, Jordan is not visible today – too much dust.

As I trek up one more slight hill and then begin descending on the other side, Al-Aqsa Mosque towers above the landscape – and then the Mount of Olives in the distance, seemingly over its shoulder. The sun is spreading a pale orange blanket on the sky, on a sheet of pink. There is the occasional honk of a car horn somewhere beyond the bend.

When I arrive at the site, I hear the drone of a mechanical arm rising over the excavation site. It’s lifting a couple giant bags of soil and rocks, liberating them from the burden weighing on them for thousands of years. I watch for a moment and absorb the scenery all around, breathe deeply. Enough. Set your bag down and let’s go. Shoes thump on the wooden walkways as we descend to our cubicles of stone and dirt.

From above, the site reminds me of a fair, with temporary tents set up all around. These elevated, netted shades provide us a haven from the sun. The minutes pass as I remove the gray dirt – more like dust in this spot – from a pit.

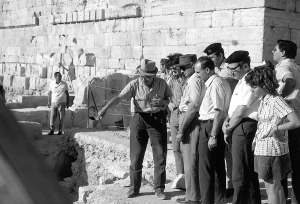

A little later, a convoy of tourists pass the stretch of fence besides our area. Hats, cameras, sunglasses – and most dressed in white, it seems. I continue digging, but overhear the din of sounds as they point and comment. On a few faces, glasses lower as they gaze through the fence. The line is soon gone. Then, the area supervisor walks beside our square, which is steadily lowering. His assistant is with him. They converse in Hebrew about the area beside me. I continue working, dumb to the insights, until he begins speaking to me in English.

Several meters away, a stone reverberates with a low hum as a dust-covered worker pounds a breach in a stone wall. Before long, a bell rings from above, as if children were being set loose for recess from the classroom. My area supervisor overlooks the dig site from a preserved tower, like a watchman. He calls “Hahf-seh-kah!” It’s break time. Workers from various heights and platforms scamper up, up.

We share conversation over some tea during the break inside a few ancient, open-air rooms of a Byzantine structure – almonds and cookies too.

Then it’s back to the dirt and rubble. We set out to remove the very Earth from beneath our feet. It’s a huge undertaking and it takes every back, every hand, the effort of all. From the echoing hollow of a room out of sight, I soon hear – in a New York accent – “Sha-shehr-eht!” Chain. It’s time for the bucket line.

The bell again. The second time bell means lunch. The gathering to the break area develops even quicker this time.

Another hour or two of getting closer to history… Before closing the “office,” we hear the Muslim prayers and calls to prayer resound through the valley of Kidron to our east. The sound booms as it’s voiced from the speakers at the crown of a minaret.

We’re eager for what will develop. I expect a lot more hopeful sights and sounds yet to come.

The Ophel Road is the southernmost boundary of our dig site. We exit along this road every day. It’s common to witness a clogging of the traffic – and when that happens you can expect the horns to sound in a major way. For a few of the students, when they’re out of the gate, they’re off to the races. It’s a 25 minute walk, but only a 15 minute run – so why not?! “See ya!” It’s over, but we’ll be right back at it tomorrow.

Take a look before you go. One of us shot this video with our phone as we passed near the Dung Gate – a gate just a little farther to the west, leading directly north to the Western Wall. It’s a bar mitzvah!

- Diggers on the trek to work – facing eastward.

- Walking party traverses the high, western hill of ancient Jerusalem.

- The crew near the Dung Gate, approaching the walking toward Ophel Road.

- Arrival: near entrance to Ophel Excavation on the Ophel Road.

- Laskey Hart, AC Student, strikes the earth with a deft blow.

- Jessie Hester fills buckets with bone-dry soil.

- AC student Chris Eames reveals the past with his pick.

- AC students and alumni in Jerusalem headed to the Ophel excavation.