Dr. Eilat Mazar, Queen of Jerusalem Archaeology, Has Died

Preeminent biblical archaeologist of Jerusalem, Dr. Eilat Mazar, died on May 25 at age 64, after a three-year battle with a serious illness. Dr. Mazar leaves behind a rich legacy of biblically significant discoveries including the discovery of King David’s palace, Nehemiah’s wall, the Solomonic gate of Jerusalem, as well as numerous discoveries related to biblical figures.

An indomitable woman of strength and determination, Dr. Mazar unabashedly believed the Bible to be the most important source in excavating ancient Jerusalem. And when the discoveries in the field matched the contents of Scripture, Dr. Mazar never refrained from “letting the stones speak.” As such Dr. Mazar was a champion of true scientific discovery in ancient Jerusalem.

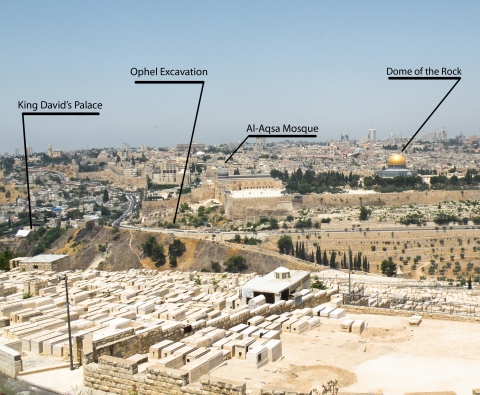

During Dr. Eilat Mazar’s archaeological excavations in ancient Jerusalem, four biblical personalities were confirmed as being historical figures. In the City of David, Dr. Mazar discovered the seal impressions belonging to two of the Prophet Jeremiah’s accusers, Gedaliah son of Pashur and Jehucal son of Shelemiah, both mentioned in Jeremiah 38:1, and uncovered in 2005 and 2008. In 2009, while excavating on the Ophel, an area just south of the southern wall of the Temple Mount, Dr. Mazar uncovered the seal impressions of King Hezekiah of Judah and Isaiah.

The seal impression of King Hezekiah, which released to the public in 2015, remains the only biblical king of Judah ever to be discovered in controlled scientific excavations. Its discovery was also the personal highlight of all of Dr. Mazar’s long career of excavating Jerusalem—one that spanned five decades.

As a small child, Eilat worked alongside her grandfather, the late Prof. Benjamin Mazar, on the Temple Mount excavations. Benjamin Mazar was a founding father of the modern Jewish state; he was central to the establishment of Hebrew University and the Israel Exploration Society, as well as numerous other intellectual and public institutions.

As a child, Dr. Mazar visited archaeological digs all over Israel. Together with her sister (Tali), young Eilat would serve tea and coffee at her grandfather’s weekly living-room gatherings of Israel’s most important figures. When Eilat finished her mandated stint in the army, she literally ran to the admissions office at Hebrew University. She studied archaeology and the history of the Jewish people.

In 1981, after attaining her bachelor’s degree, Eilat participated in the City of David excavations directed by Prof. Yigal Shiloh from 1981 to 1985. Within a few weeks of starting work, she was given her own area to supervise. For her master’s thesis mentored by Prof. Nahman Avigad at Hebrew University, Eilat studied the First Temple period finds from the prior excavations of the Ophel area just south of the Temple Mount’s southern wall.

In 1986, Eilat convinced her grandfather to return to the field and join her as codirector of a small excavation at the southernmost area of the Ophel. Benjamin agreed and almost immediately the pair discovered remains of the First Temple period gatehouse (the first ever discovered in Jerusalem). In 1997, Dr. Mazar attained her Ph.D. from Hebrew University for a comprehensive pioneering study about the biblical Phoenicians based on her ongoing excavations (which began in 1984) at the key Phoenician site of Achziv (northern shore of Israel).

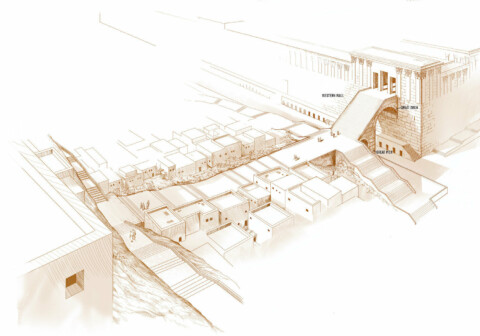

In 1997, Dr. Mazar wrote an article for Biblical Archaeology Review suggesting the location of King David’s palace based on the description in 2 Samuel 5:17 that King David “went down” into his city. She hypothesized that the ruins of David’s palace must be in the northern part of the City of David. In 2005, she received funding and permission to start an excavation. Within weeks, Eilat had uncovered massive walls, indicating the presence of a large structure, which dated to King David’s period.

Dr. Mazar conducted three phases of excavations in the City of David between 2005 and 2008. She uncovered more evidence of David’s palace, as well as other remarkable artifacts supporting the biblical record, including the seal impressions of two biblical figures mentioned in Jeremiah 37 and 38, as well as a portion of Nehemiah’s hastily constructed wall (Nehemiah 6:15).

In 2009, Dr. Mazar returned to the Ophel to excavate. This dig and three more excavations (2012, 2013, 2018) have uncovered some extraordinary history. Discoveries include a massive city wall from King Solomon’s time, the Menorah Medallion treasure, dozens of coins relating to the first-century Jewish revolt, and two biblical seal impressions: one belonging to King Hezekiah of Judah and the other belonging to Isaiah.

With Dr. Mazar’s death today, Jerusalem loses its queen of biblical archaeology. Nevertheless, the significance of her discoveries will resonate for years to come. She will be dearly missed on the excavations in ancient Jerusalem and in the hearts of all those she has touched with her passion, sincerity and grace. Most notably, her sister, daughter and three sons.

We are deeply saddened by her death, but will endeavor to uphold her legacy as well as her archaeological method and let the stones of ancient Jerusalem continue to speak.